HEALTH and death in the beautiful Washburn Valley come under the spotlight in a fascinating exhibition.

Our Natural Health Service will run at the Washburn Heritage Centre until the end of May and includes a programme of events.

In the following piece Christine Pearce, from the centre, takes a look at some of the stories from the exhibition.

After two years of science, statistics and anxiety about health, the Washburn Heritage Centre’s spring programme looks at how our beautiful natural environment and our own resourcefulness can be put to service to improve our health.

Part of our planning was to look backwards, the extensive archive collection at the centre being one port of call. We found out more about the Washburn Valley’s contribution to better health and concluded that lessons HAD been learnt from the past.

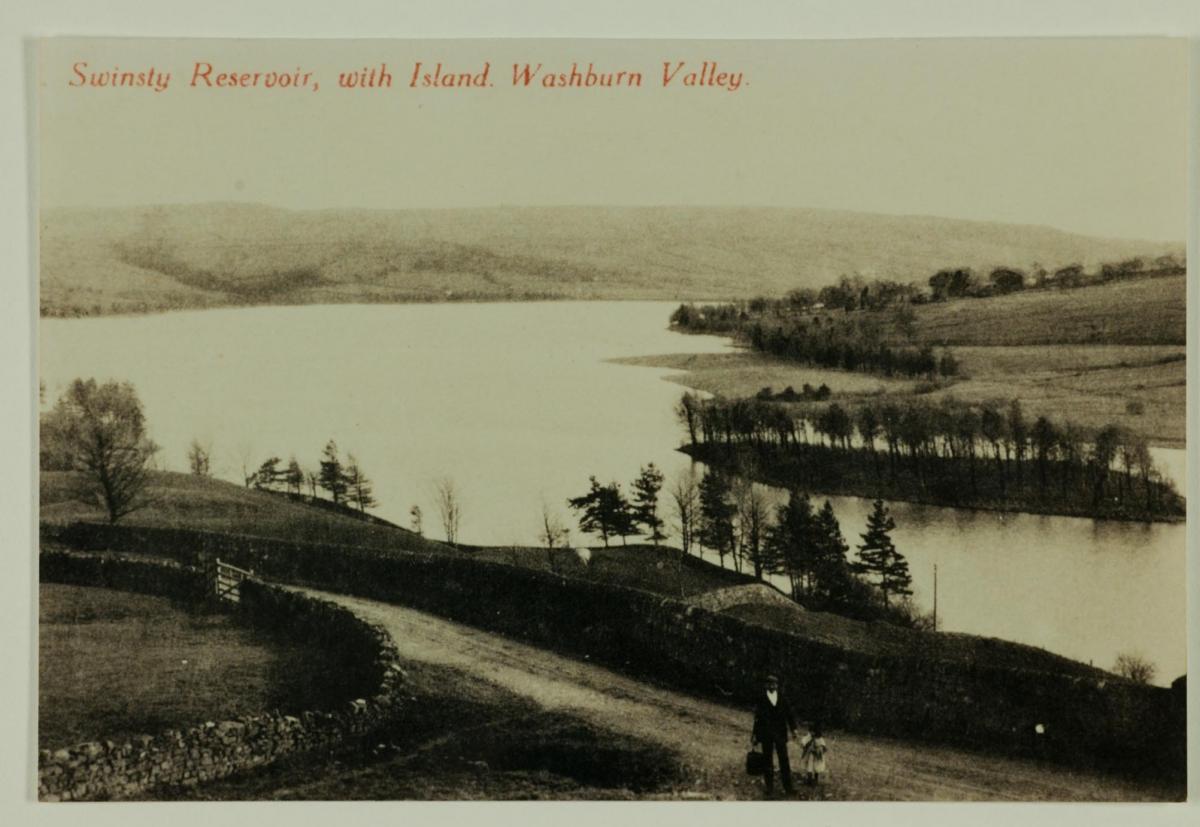

In the nineteenth century the pellucid water of the Washburn valley was seized upon by the growing city of Leeds and the beautiful Washburn Valley is now home to a chain of reservoirs providing clean water for Leeds.

A former vicar of St Michael and St Lawrence Church, Fewston famously said, “Fewston must die so that Leeds may live.”

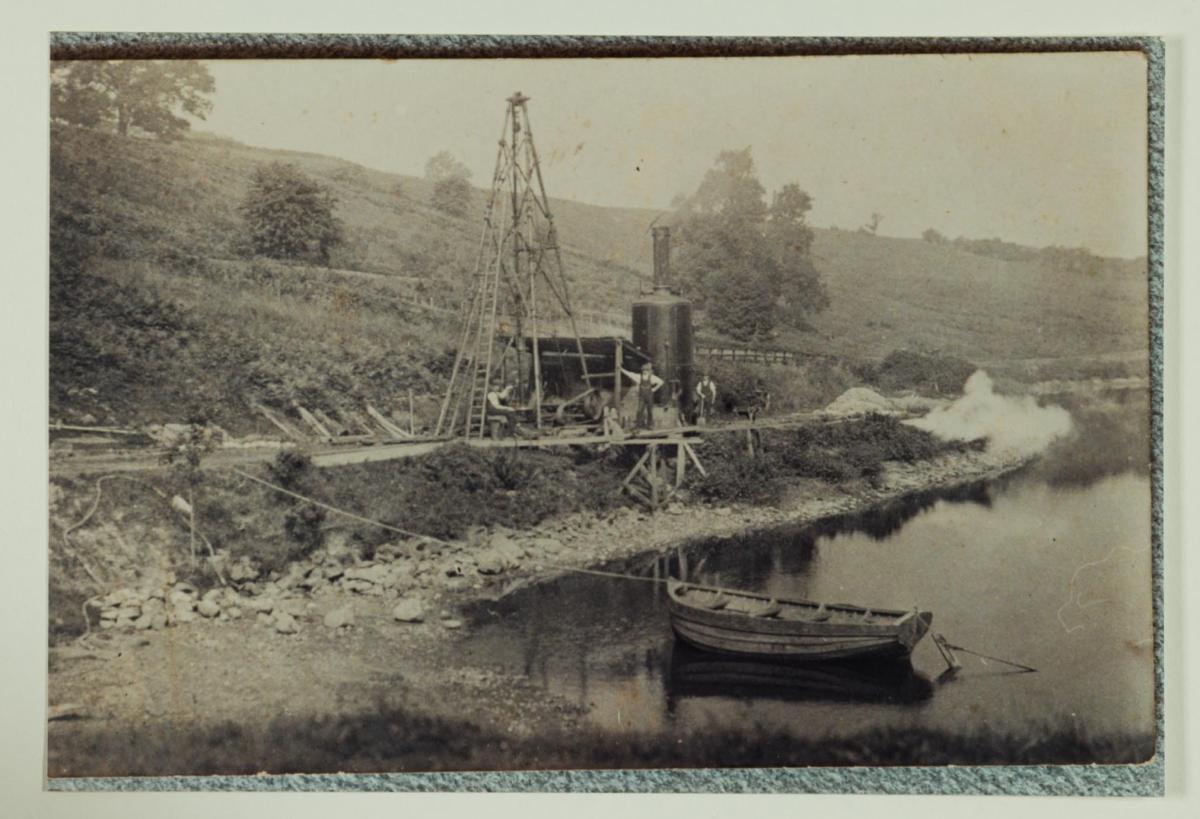

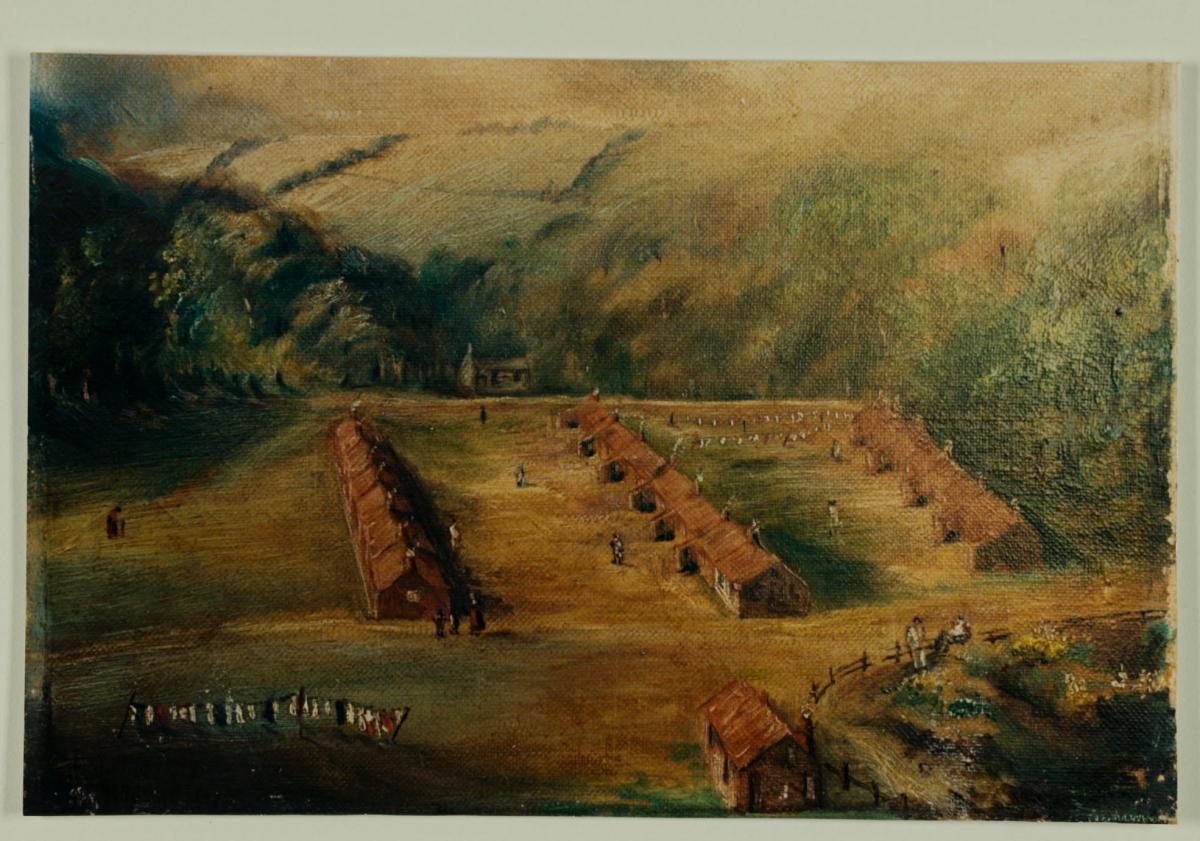

The first reservoir to be built in valley was the Lindley Wood Reservoir in 1869-72 and a navvy camp was built to house those who worked on the reservoir. Conditions were cramped and sanitation in the camp was very basic. That clean water for was needed as our forebears had to worry about water borne diseases.

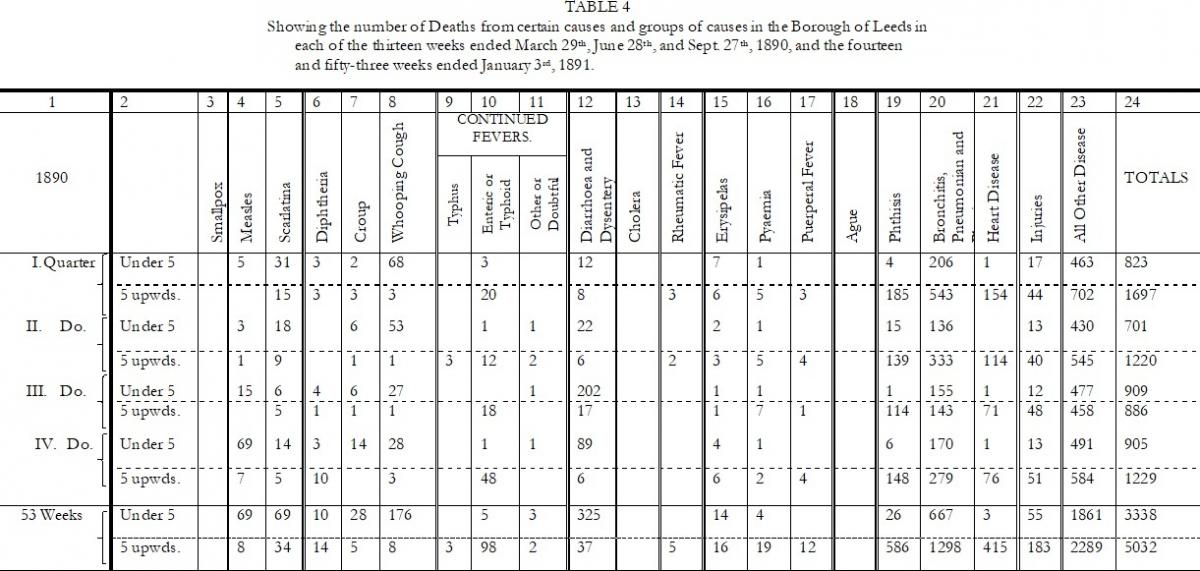

An extract from Leeds Health Report in 1890/1891 shows infant mortality by cause of death, with occurrences of diarrhoea and dysentery being high. Thanks to Ken Fackrell for transcribing the table from the health report. There are causes of death on this extract that we, in the 21st century, may not be familiar with which is a success of modern, and not so modern medicine. The archaic medical term Phthisis might now be called pulmonary tuberculosis or a progressive wasting disease. It is now quite treatable with special, targeted anti-tuberculosis agents.

Erysipelas is a superficial form of cellulitis, a potentially serious bacterial infection affecting the upper layer of the skin. In the twenty first century it is unlikely that anyone in this country would suffer erysipelas as modern antibiotic treatment would prevent such a severe infection taking hold. However, Washburn Valley did have at least one nineteenth century sufferer of erysipelas.

In 2009/10, before the Washburn Heritage Centre was constructed, it was known that the area to be excavated held several sets of human remains. Thanks to Heritage Lottery Fund grants these skeletal remains and artefacts were removed and examined by archaeologists at the Universities of York and Durham, before being reinterred at Fewston, and are now known as the Fewston Assemblage. Volunteer researchers from the centre collaborated with professional teams and gathered information about the 154 individuals. One such person was Elizabeth Dibb. She had lived in the valley from 1843 having married a farmer. In June 1890, shortly after the death of her husband, Elizabeth was admitted to the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum which was also known as High Royds, in Menston. Two of Elizabeth’s daughters were already patients at the same institution. She was suffering with poor mental health due to a combination of factors and possibly caught erysipelas whilst a patient. The condition was the MRSA of Victorian times.

She died at 7.10 am on April 26, 1892, aged 71 from ‘atrophy of the brain and erysipelas of the face’. It is significant that Elizabeth was brought back to Fewston to be buried with her husband, James, rather than being buried in the asylum cemetery. Understanding of mental illness was limited in the nineteenth century and treatment woeful. These days we appreciate that time spent in the great outdoors including around the Washburn Valley can be an immediate boost to your wellbeing. We have also learnt that incarceration is not appropriate for many conditions.

If you visit the Washburn Heritage Centre you will see this attractive facial reconstruction of Elizabeth commissioned from Liverpool John Moores University after a grant from the Liz and Terry Bramall Foundation was received.

Our final dip into the photographic archive revealed Catherine Hardisty and daughter, Ethel Hardisty Holmes both looking out proudly wearing their very smart nurses uniforms. We smiled as in the first lockdown in 2020 our TV screens were filled with mask and apron wearing health care staff and several of our volunteers had sewed scrubs at that time. We think Catherine and Ethel’s generous capes and headwear would now be considered as super spreaders of germs.

To find out when the Centre is open and more about our Spring programme visit www.washburnvalley.org

All images ( except High Royds) copyright the Washburn Heritage Centre.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here