IN the wake of the FA ban the women’s game of football has been described as being placed in a state of ‘suspended animation’ and despite their best efforts, the fate of Hey’s Ladies is representative of that process.

Until the revival of women’s football in the 1980s, the game in Bradford was reduced to one off events such as the floodlit 1953 match between Preston Ladies and Manchester at Odsal Stadium.

On a purely local level, occasional charity games between women’s teams continued to take place. One example being the 1956 game between the Queen Tigers, from the Queen public house on Thornton Road, and a team from Fairweather Green Working Men’s Club. The game raised £12 10s for Fairweather Green WMC annual children’s treat.

According to newspaper reports the match was a lively affair with much screaming and hair pulling. At one point both goalkeepers were reportedly embroiled in a fight for the ball.

Why did women’s football become a popular spectator sport and why was it confined to a relatively brief period?

There was a linkage with the First World War and the fact that the game had a social purpose that enabled women’s football to side step the constraints imposed by gender politics and stereotypes.

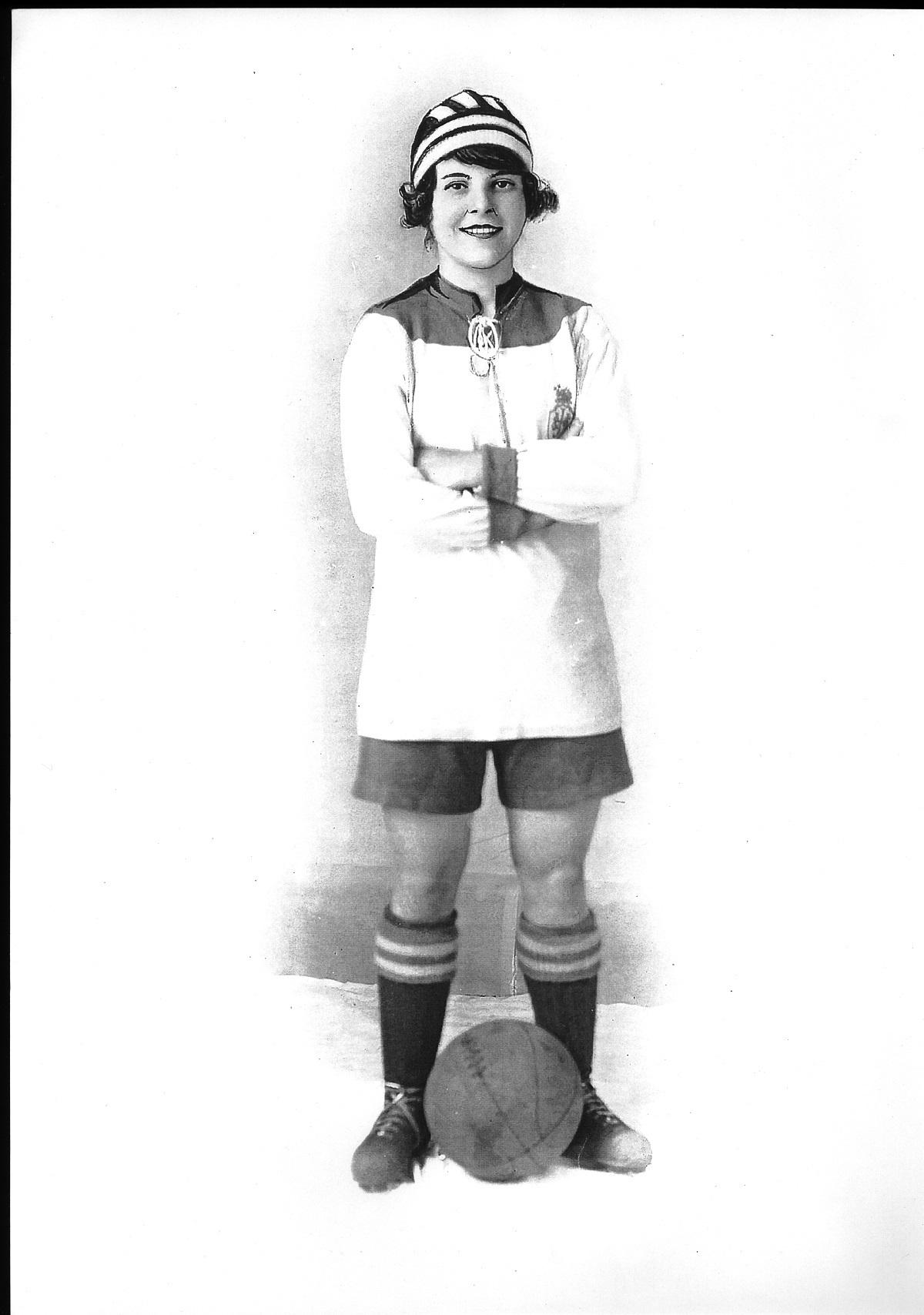

In particular, the tapping into the narrative of the ‘plucky heroine’ that emerged during the Great War as women were ‘thrown into traditional male roles at home, in the work place and on the sports field’, meant that games during this era avoided condescending and hostile perceptions that have dogged women’s football.

It has been argued that spectators were more receptive because the matches were charitable events that raised money for the families of soldiers killed or wounded at the front.

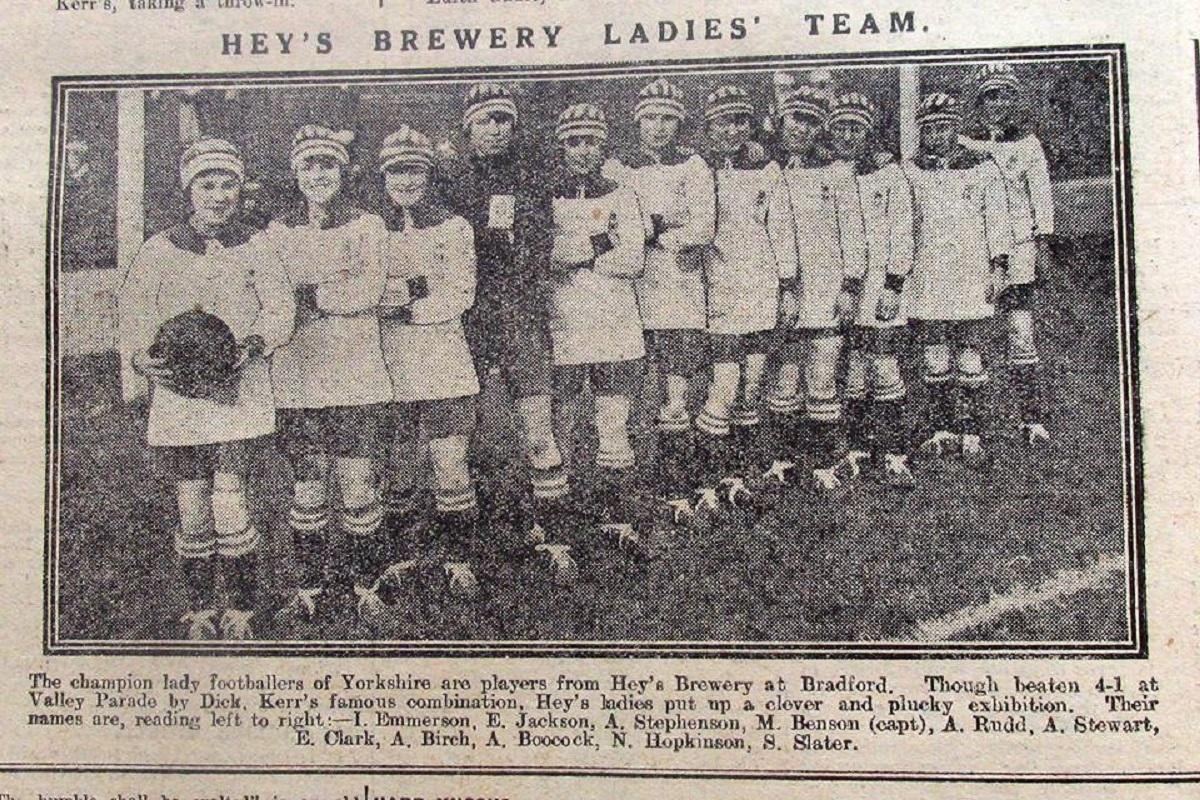

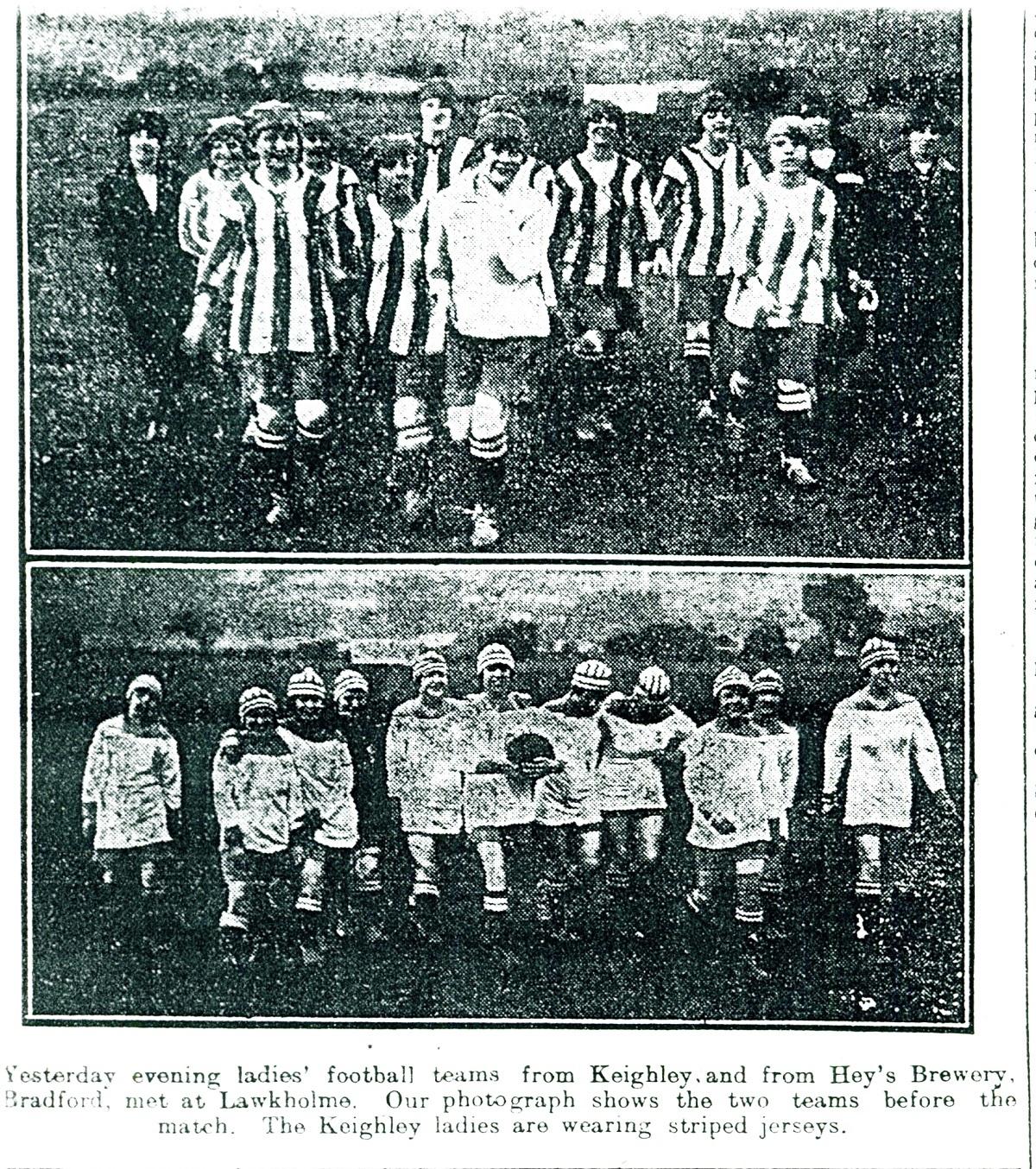

Hey’s prowess on the field of play, the meeting of the English Ladies FA at Bradford in 1921 and the abortive attempt to host the 1922 English Ladies FA Challenge Cup Final, illustrate that Bradford was one of the key locations of women’s football after the Great War.

Hey’s Ladies adoption of cricket in 1925 may reflect the pressures brought to bear on the management of Hey’s Brewery,

who were also involved at board level with Bradford City AFC during the same period, by the FA ban.

It could be argued that, disenchanted by the politics of football, Hey’s turned their back on the game and took up cricket instead. Perhaps cricket offered an extension of the camaraderie that sport had offered them?

Hey’s Ladies first reported cricket match was played against a team from the Bradford Dyer’s Association. Hey’s Ladies scored105 for the loss of four wickets.The Dyers’ Association side was all out for nine.‘Tiny’Emmerson (a winger from the football team), took seven wickets for seven runs. Margaret Whelan (scorer of several goals forHey’s Ladies) captured three wickets for two runs.

The team played in the Bradford Ladies’ Evening Cricket League. In 1931 they won all four cups offered in Bradford.

However, the fact that the social context of women’s football’s charitable role and workplace emancipation had lost some of its focus by the early 1920s could also have been a factor in why it was confined to a brief period.

It could be argued that the subsequent chaotic and light hearted matches, as represented by the 1956 game at Fairweather Green, represented the ultimate victory of those who sought to crush women’s football in the wake of the Great War. The high minded ideals of charity, emancipation and solidarity had fallen a long way.

The fact that the FA’s ban on women’s football was not lifted until 1971 reflects poorly on, and asks uncomfortable questions of, the so-called people’s game.

Even after the ban was lifted it was another decade before women’s football began a long overdue rehabilitation.

However, a century on from Hey’s appearance in international matches - perhaps at long last the Champions of Yorkshire - from a brewery bottling plant can begin to take their rightful place in the sporting and social history of Bradford and beyond.

* This completes our series of features on the story of Hey’s Brewery Ladies, who went from playing their first match at a park gala to representing England. The team, all workers at Joseph Hey & Co Ltd on Lumb Lane, were pioneers of the game, despite the 1921 FA ban on women playing at Football League grounds.

* This article was written in conjunction with Malcolm Toft, writer of articles for the Brewery History Society and Bradford

CAMRA, and historian Michael Pendleton.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here