IT is twenty years this year since Craven was brought to a grinding halt by an outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the country.

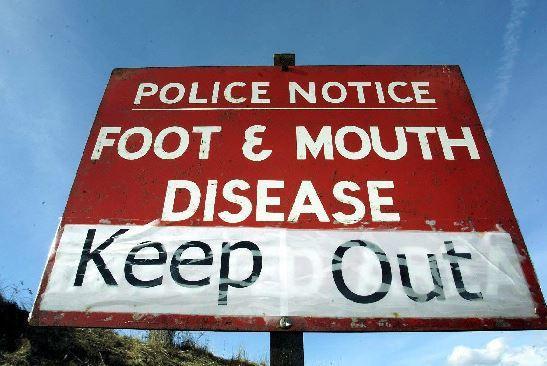

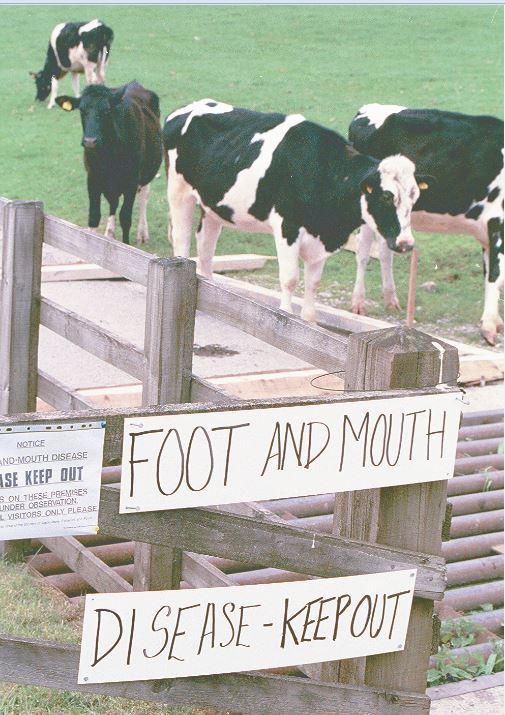

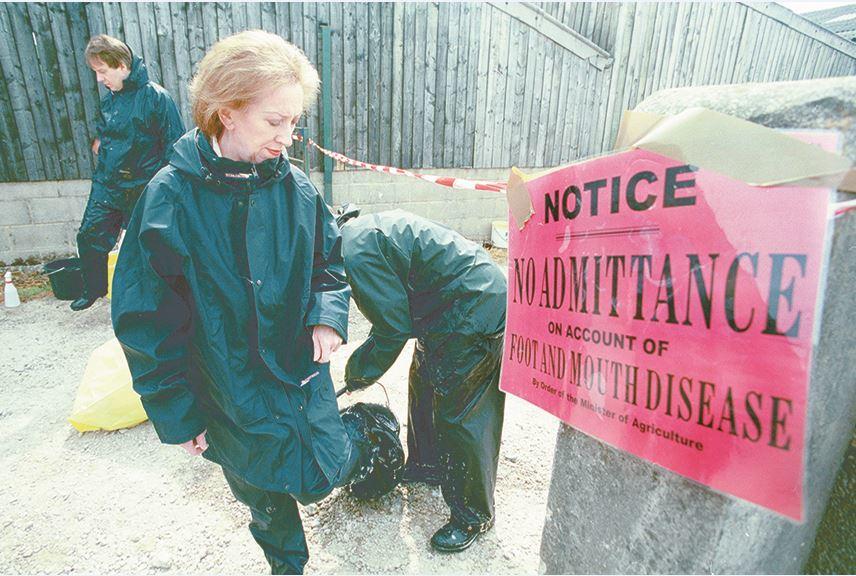

In February, 2001, footpaths were shut, events and sporting events stopped and sales of animals banned.

Two decades ago the auction mart was stopped from opening. It would be 12 months before sales started again, causing huge anguish for farmers.

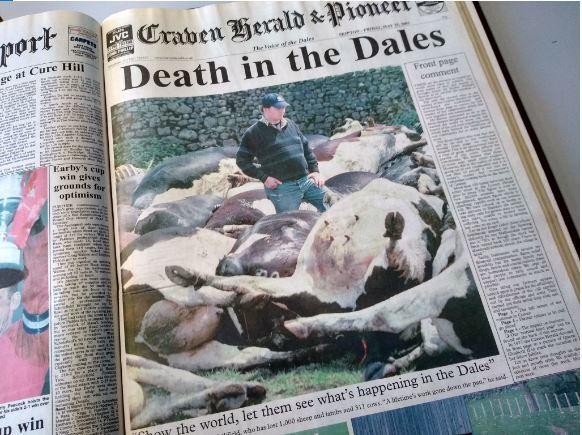

For only the second time in its long history, the Craven Herald abandoned its traditional front page adverts and replaced it with the heartbreaking picture of Hellifield farmer Richard Barron standing among his herd of dairy cows which was slaughtered as a contiguous cull.

The first occasion adverts were replaced was to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.

On that fateful day in Hellifield, Mr Barron would lose 337 cattle and around 900 sheep.

Around Craven at the time the district’s economy was in freefall. Exclusion zones around the district meant sports matches had to be cancelled, anglers were banned from rural riverbanks, shows were called off and tourists were told to stay away.

Craven was surrounded by the virus – with outbreaks reported in Hawes, Queensbury and Great Harwood.

But the district managed to ward off an attack until Thursday, May 11, 2001 when it was announced that clinical signs of the disease had been found at Cowside Farm, on the hills above Langcliffe. Nationally, it was case number 1,575.

'Death in the Dales' was the distressing headline the Herald carried on May 25, 2001 to highlight the effect the foot and mouth epidemic was having on our farmers.

The message was so serious it shifted the traditional front page adverts of the paper to the back and instead carried a photograph of farmer Richard Barron, of Swinden Farm, Hellifield, standing among his dead stock.

The day is etched into Mr Barron’s memory when men ordered by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) arrived at his farm to wipe out his life’s work. It was Tuesday, May 22, 2001.

“I remember it as if it was yesterday,” he said. “Ironically, it turned out that the farm we were contiguous to was found to be negative. We never had the disease here.

“Another farm nearby did eventually get it, but at the time our animals were killed it wasn’t here.

“I milked that morning so the animals would not be in too much stress. It was so heartbreaking I couldn’t milk my best cow. She was a fantastic milker and a fantastic looking animal; a show winner. I got a farm helper to milk her for me.

“Foot and mouth was devastating to the farming community. “We got paid out, yes, and it seemed like a decent payout, but what people didn’t realise was that payout didn’t cover the loss of earnings from that herd over the next year and beyond.

“There was the cost of the constant cleaning we had to carry out too. I’d say we spent at least £100,000 on cleaning.

“Farmers couldn’t just go out and get more animals as replacements either because of movement restrictions as well as increased availability. When we did, which wasn’t until the following March, we had the added problem of keeping cattle healthy that had come from elsewhere and were not used to the land.”

Mr Barron said an example of the problems farmer’s had was when he bought 78 cows one day and brought them back to the farm. Eighteen months later there were just 36 left.

“Some just didn’t thrive on different land, whether it was a difference in vitamins or exposure to different illnesses they couldn’t cope with, or what? We had vets’ checks and all sorts but some just didn’t do. That was something a lot of people didn’t realise.

“And then there were those farmers who never had animals culled but couldn’t move them or sell them because of the restrictions and it was costing them a lot of money to keep them on. Either way foot and mouth put a lot of farms out of businesses.

“Foot and mouth was destroying farmers’ futures and the government at the time didn’t have a clue. Some of the things they did were farcical.”

Mr Barron was happy for us to take photographs of that upsetting day on his farm.

He said he wanted to ‘show the world what is happening’.

Foot and mouth started in Essex on February 19, but it soon spread and within a fortnight all of Craven’s footpaths, bridleways and public rights of way were locked down.

After that first case was alerted in Langcliffe on May 11, the situation rapidly deteriorated and within a week seven more cases were confirmed in North Craven, resulting in the slaughter of 22,000 animals.

“Many farmers have just been left waiting while decisions are made on neighbouring culls. The worst thing is that they just don’t know what is going to happen,” said Stephen Dew, of the National Farmers’ Union, at the time.

By the time Richard Barron’s animals were killed there had been 18 confirmed local cases with livestock culled at 97 contiguous farms. The number of slaughtered animals was now more than 80,000 in Craven alone.

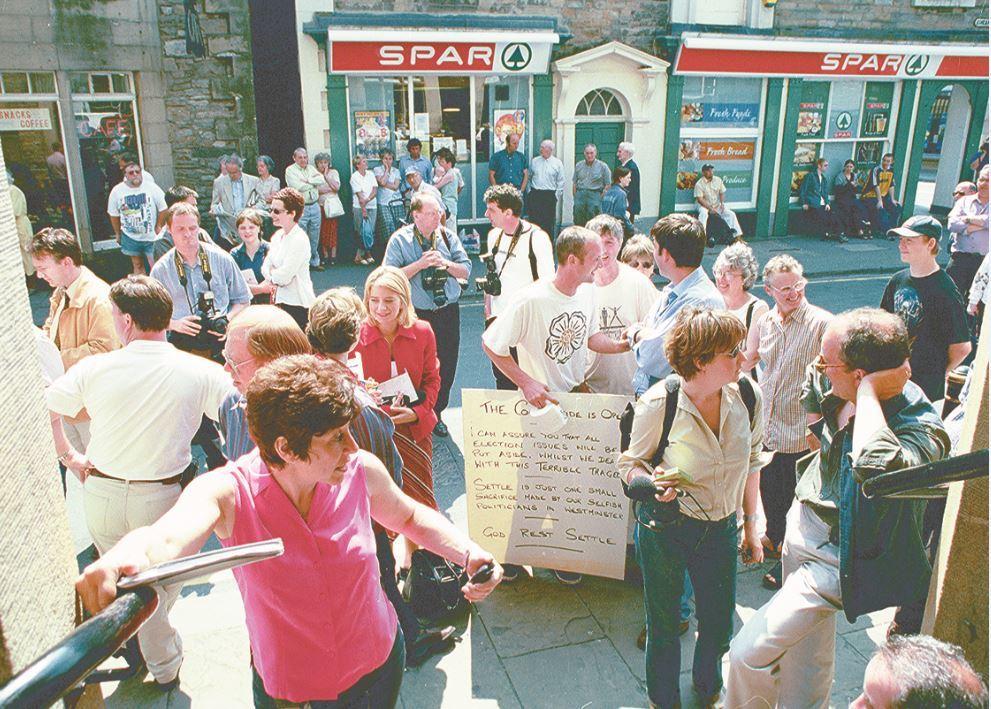

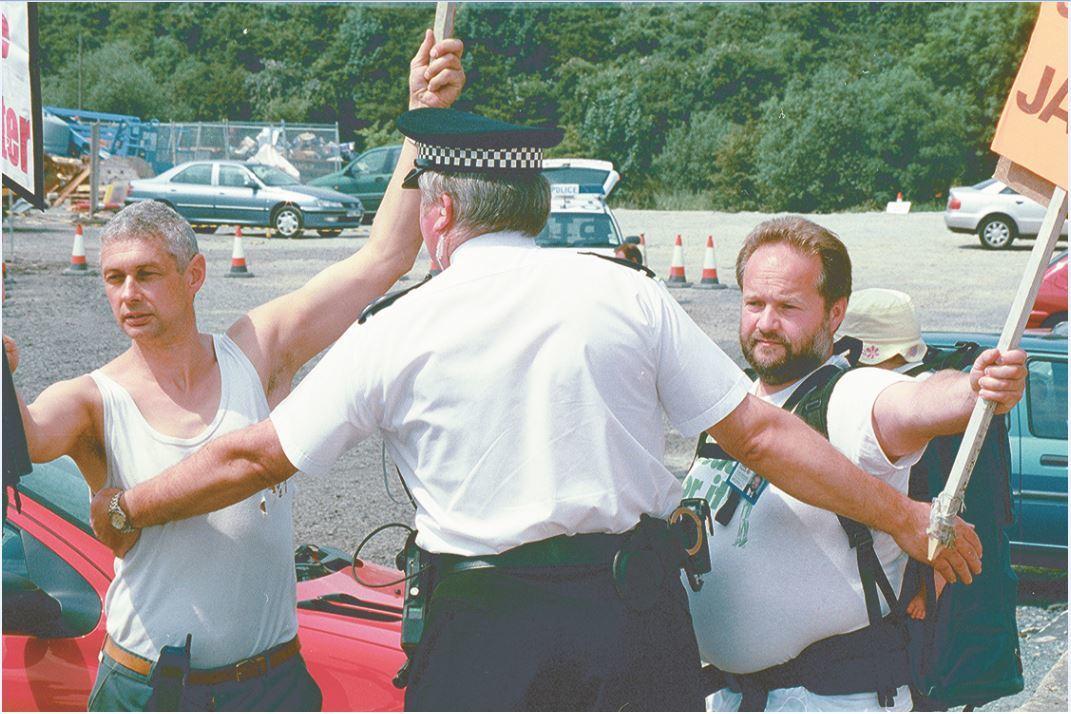

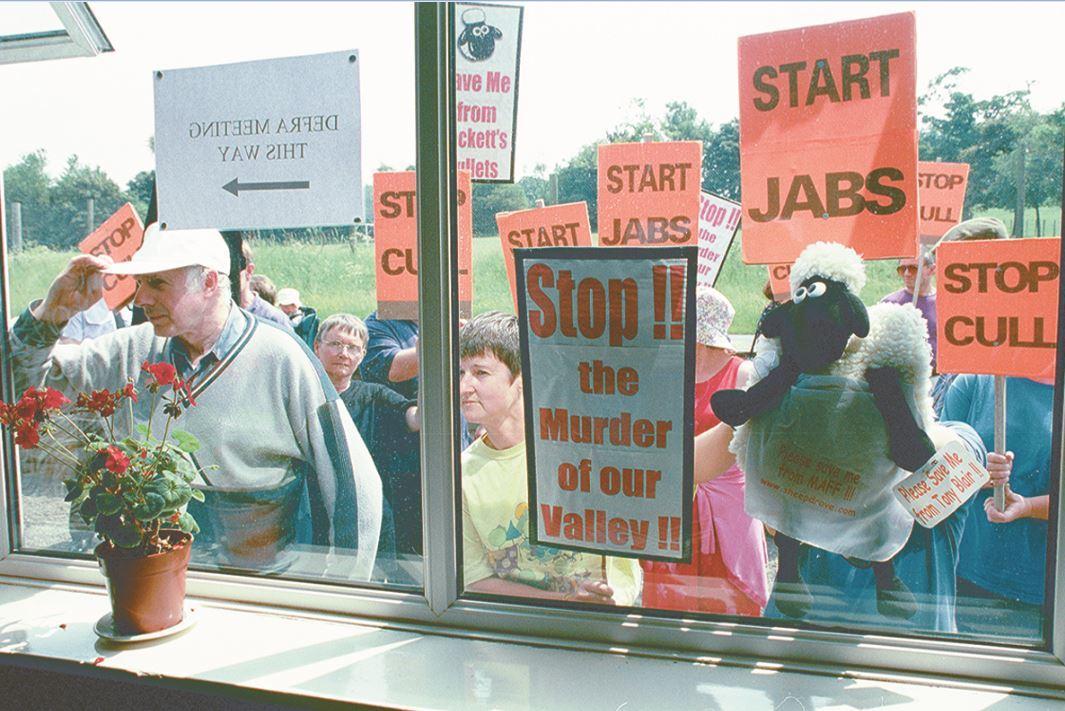

Agriculture Minister Nick Brown had visited Settle in a show of solidarity, but he was heckled by angry residents. He tried to reassure the public the Government was doing everything it could to eradicate the disease, but his words did little to ease the worries of onlookers.

By the following week, foot and mouth had reached Upper Wharfedale, with Kail Farm at Thorpe becoming Craven’s 27th confirmed case.

The spread of the disease was relentless, and among its next victims was a herd of water buffalo being farmed by Matt Dinsdale, at Wigglesworth.

Soon the number of cases had reached 55 and local charity, the Craven Trust, launched the Dales Recovery Fund to help those affected.

But it was not just farmers who were suffering. Local businesses were also struggling to survive. One example was Halton West agricultural feed manufacturer Henry Waddington, which had seen its trade fall by 85 per cent. As a result, two of its 10 workers were laid off.

The Prince of Wales pledged his support for the area in a letter to Craven District Council chairman, Coun Stephen Butcher.

Written by his secretary, the letter said: “His Royal Highness has a special affection for the people and landscape of your remarkable and unique part of England and he has shared in the anguish which so many must be feeling as the scourge of this disease has continued to spread.”

By the end of June, there was optimism. There had been no new cases for a week, and Defra’s director of operations, Dr Stephen Hunter, told a press briefing that he felt the disease was at last being brought under control. “However, I do expect there to be sporadic cases appearing over the next few months and high standards of bio-security should be maintained.”

Sadly, the optimism was short-lived, as the disease moved into South Craven and returned to Upper Wharfedale and North Craven.

On July 27, the Craven Herald reported that Croft Closes Farm at Giggleswick, owned by Alan and Theresa Butler, had become the 100th infected farm in Craven.

Meanwhile, Craven District Council released the findings of a survey of 3,000 businesses, which showed the tourism sector had already lost an estimated £19 million through foot and mouth, and if the present trend continued, the figure could reach £38 million.

Council leader Coun Chris Knowles-Fitton said: “Foot and mouth has been a catastrophe to all sectors within Craven, including agriculture, tourism, communities and public services.

“We must pull together to rebuild confidence and work with regional and local partners to plan and implement the recovery.”

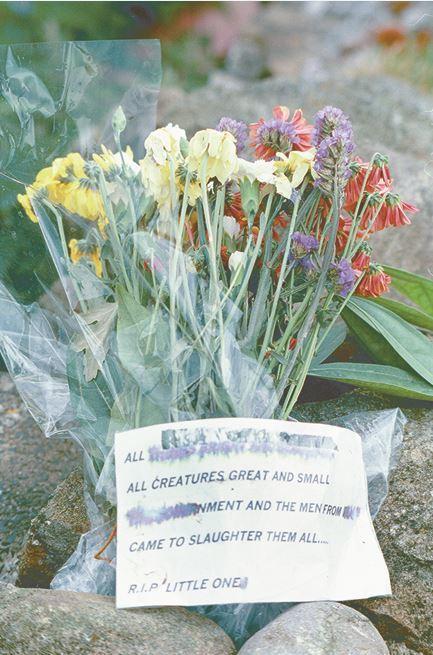

Around the Dales people wept for the animals while businesses struggled.

Farmers were bewildered, especially Philip Metcalfe, of Otterburn Hall Farm, Bell Busk, who saw 1,222 sheep and cattle slaughtered through a Ministry blunder. MAFF had killed the wrong animals.

Elsewhere, protest were held in towns and some farmers even blocked roads to stop transporter wagons getting through.

Distraught residents were leaving floral tributes at the side of roads for the culled animals and farming couples, such as Susan Read and Jeremy Stockdale postponed their May 26 wedding with only six days to go after the disease his Coniston Cold where they were to hold their wedding reception.

Protest groups gathered petitions against the culling and hand delivered them to Downing Street.

Chef Richard Wallbank, who had only just opened his Settle restaurant, Ravenous, was despairing after ploughing all his money into the venture only to find Settle turned into a ghost town.

Government Ministers came to the region to hold press conferences and try and quell fears that what was being done was ‘for the best’.

Part way through the epidemic, government changes saw MAFF become DEFRA (Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Because it was in the days before social media, vicars who were unable to organise church congregations were forced to offer their flock comfort over the telephone.

Eventually, foot and mouth outbreaks came to an end. The last infection was recorded on August 16 at Chandlers Cote Farm, Addingham. It was the 102nd case.

The district counted the toll it had had on farms.

Since the outbreak, Craven had seen 416 contiguous premises culled and 43,365 cattle had been slaughtered, along with 242,501 sheep, 182 pigs, 66 goats and 155 exotics, including farmed deer and buffalo.

It was another four months – at midnight on December 31 – that Craven was officially declared foot and mouth-free.

However, the 11-month nightmare had taken its toll and, for many, the journey towards recovery would be a slow and painful one.

Across the country, 2,000 cases of the disease were recorded and more than 10 million sheep and cattle were killed to halt the disease.

By the time the disease was halted, the crisis was estimated to have cost the United Kingdom £8 billion.

As the country today battle’s against two viruses - Covid-19 and Avian Flu, Skipton Auction Mart general manager Jeremy Eaton reflects on the future saying: “There are similarities between the days of foot and mouth and the situation we find ourselves in today, though with one major difference.

“On this occasion we are able to keep trading as an essential business, whereas we were unable to trade at all during foot and mouth. There was farm-to-farm trade only for those who were able, which completely removed competitiveness and left farmers vulnerable on price. However, once live markets resumed people could buy what they wanted from a central point and both the balance and competitive edge were restored.

“That remains so today because here we are 20 years on facing similar difficulties, but still managing to ensure that stock is sold as competitively as possible, at the same time moving on animals as quickly and efficiently as possible.

“We are also looking to the future by putting in place building improvements that will equip us a market fit for the next century, a commitment that will see us remain one of the leading livestock marts in the country.”

The previous outbreaks of the disease had occurred in 1967.

We would hope, with advances in sciences, success in developing vaccines and treatments for other diseases such as bovine TB, that should foot and mouth return, it can be dealt with differently.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here