He is arguably the most influential person ever to have lived in Burley-in-Wharfedale. And his philanthropic views have had a significant impact on the village and the surrounding area.

But more than a century after his death, many people have no idea who William Forster was or what he stood for.

Last week the spotlight fell on the eminent Victorian again as Burley historians Dennis and Margaret Warwick launched an appeal to find his missing headstone.

Mystery surrounds the fate of the headstone detailing the life and death of one of this country’s most influential statesmen who became an MP in 1861.

The granite stone, in God’s Acre Cemetery, Burley-in-Wharfedale, had lain untouched in the graveyard for a century but in recent years it vanished from the site.

Mr and Mrs Warwick have had a long fascination with the life of the MP and mill owner and have written a book about his life and that of his wife, Jane.

In their book, The Forsters of Burley-in-Wharfedale, they describe the life of William Edward Forster who was born in Dorset in 1818, the son of a Quaker minister.

“From them, he inherited a desire for reform and justice and a respect for dedication to duty and hard work,’’ they report.

In his early days he was active in the anti-slavery movement, and went on to become a passionate social reformer, best known for the introduction of the Education Act of 1870 which opened the doors of learning to all children over the age of five.

He was married to Jane Martha Arnold, the daughter of the liberal reforming headmaster of Rugby School, Dr Thomas Arnold, The poet William Wordsworth said of her “in all that went to make up excellence in women Jane Arnold was as fine an example as he had known’.’ The couple made their home first of all at Rawdon and then at Burley-in-Wharfedale, building a house called Wharfeside which still survives today.

Forster was in partnership with William Fison, running Greenholme Mills in Burley. He also went on to become Chief Secretary for Ireland, a post which put his life at risk during the turbulent struggle for home rule.

In their book the Warwicks say: “The location of the mill in a relatively small village, where over 60 per cent of the households had at least one member working in textiles, and the firm’s great success, obviously meant that the Forsters were regarded along with the Fisons as pre-eminent families.

“The partners were in a position to wield enormous influence over the lives of their employees both during and after working hours. They no doubt considered it as their moral duty to provide facilities which would enable the workers both young and old to use their leisure time profitably.’’ Mr Warwick said Forster believed in giving working class people the opportunity to better themselves.

His mill was highly regarded, and he sought to improve the health of the village and the health of his workforce.

Unlike many employers, Forster supported shorter working hours and believed that mill owners and workers should be partners, not foes.

Jane shared her husband’s belief in the duty of the better off to help the poor, and the couple shared a commitment to bring reformist ideas to the village.

In 1856 Forster and Fison opened their own mill school in the village, although it closed in 1897. They also built the lecture hall, a library, a reading room and a concert hall.

The Warwicks say: “Forster was the driving force behind the formation of the Local Board of Health in 1854. Burley had been transformed in the first half of the 19th century from an agricultural to an industrial village whose population had increased from 842 in 1801 to 1,894 by 1851. Increasing numbers had put pressure on existing housing and new properties had been built to meet the demand for accommodation.

“Little had been done, however, to ensure that basic amenities were provided in either the new or old workers’ houses. Overflowing privies, flooded cellars, uncleared night soil heaps and animal dung heaps were commonplace in the village in the mid-19th century. Convinced of the connection between squalor and disease, Forster and his supporters had every intention of using powers under the Public Health Act of 1848 to clean up the village.’’ Their strong sense of duty and care for others extended not just to the people of Burley-in-Wharfedale but also to their own family. The couple, who were childless, took over the care of the four orphaned children of Jane’s brother, William Arnold.

In 1861 Forster became an MP when he was returned unopposed as a member for Bradford, replacing that other great Victorian, Sir Titus Salt.

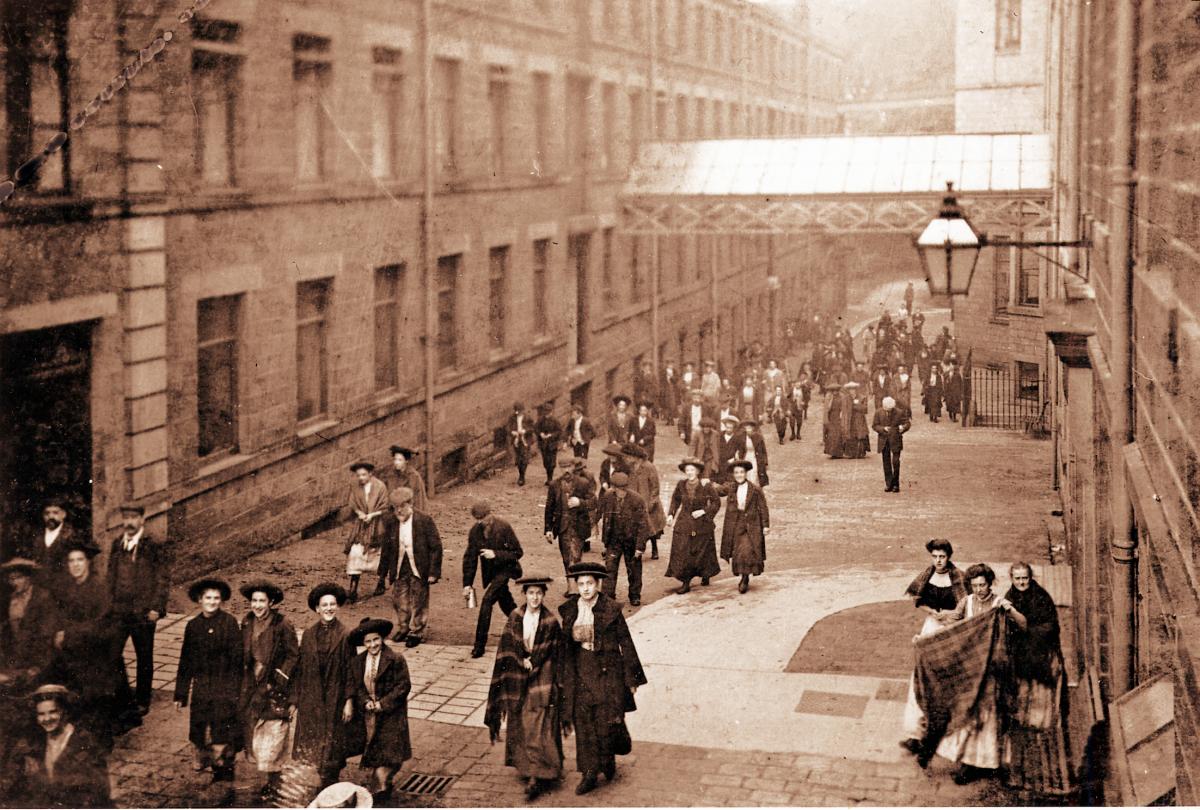

Eighteen months after he became an MP he, along with Fison, treated their workforce from Greenholme Mills to a stay in London.

In his speech introducing the Education Bill to Parliament in 1870, he said: “Upon the speedy provision of elementary education depends our industrial prosperity. It is of no use trying to give technical teaching to our artisans without elementary education; uneducated labourers – and many of our labourers are utterly uneducated – are for the most part unskilled labourers, and if we leave our workforce any longer unskilled, notwithstanding their strong sinews and determined energy, they will become over-matched in the competition of the world.’’ In 1880 he was offered the office of Chief Secretary to the Viceroy of Ireland and during his two years in the role, there were a number of threats on his life. Even on a visit to Burley in 1881, the family was guarded because of police fears over the possible actions of Irish nationalists in Bradford.

The couple’s adopted daughter, Florence, recorded afterwards “the precautions taken by the Chief Constable had been a decided reality – more so than Father at all liked; in fact, when he found 12 of the Wakefield police quartered in Burley, he sent a message to the C.C. intimating that another time he would rather be shot.’’ Indeed, he did narrowly escape death in 1882 when he inadvertently evaded a group of assassins after he took an earlier train than had been planned, on what was to be his last journey home from Ireland.

Mr Warwick said: “He would have been killed except that he caught a different train from the one they were expecting him to catch. On that last journey home he missed being killed by assassins.’’ He clearly had a lucky escape. His successor, Lord Cavendish, was murdered within days of reaching Dublin.

But, despite his lucky escape, by 1885 he was suffering from serious ill health, and he died in 1886.

His funeral service took place at Westminster Abbey, and a memorial service was held at Burley Parish Church. A brass tablet was placed on the north wall of the church in his memory. Today his name lives on as part of Bradford’s heritage – at Forster Square.

And he will be forever remembered as the man who introduced the act which opened up education to all children, whether rich or poor.

Jane lived at Wharfeside until her death in 1899. During her time in Burley she was involved in the life and charitable causes of the local community, visiting the sick, holding Sunday school classes, and taking a strong interest in local schools.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here