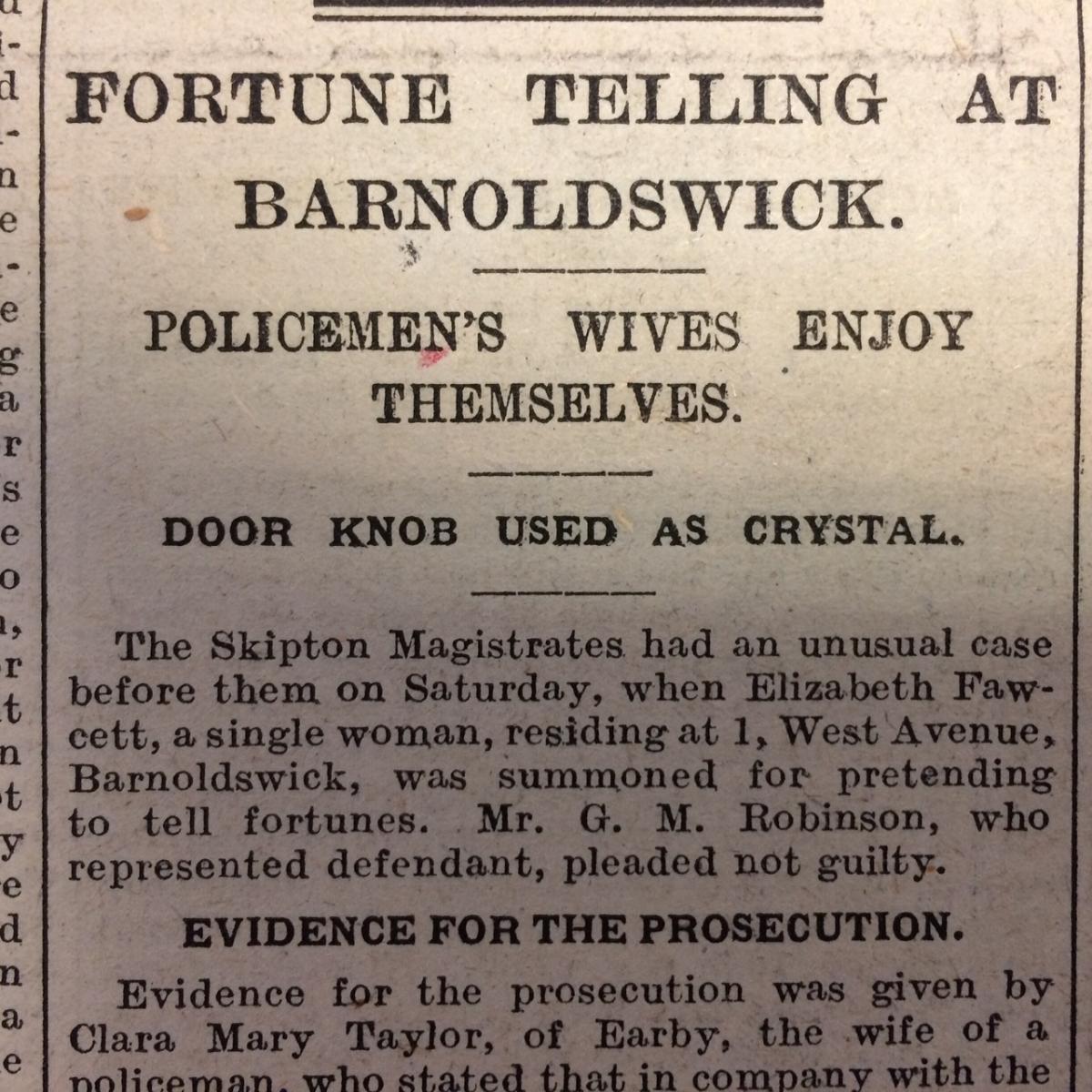

AMONGST all the endless reports of men and the occasional woman in the Craven Herald of 1917 reported dead or missing in the later stages of World War One, was a report of a fascinating court case involving a woman charged with 'pretending to tell fortunes'.

Lesley Tate reports.

IN the spring of 1917, the wives of a couple of police constables went undercover to expose the wrong doings of a Barnoldswick woman who had been carrying on a fortune telling business from her brother-in-law's home in West Street.

Elizabeth Fawcett, a single woman, was subsequently charged with 'pretending to tell fortunes' - a crime which had recently created much interest in the national press with cases in London reaching the High Court.

But, back at Skipton Magistrates' Court, it was an unusual and likely first of its kind to appear in front of the bench. The woman's defence solicitor, a Mr G M Robinson, argued that his client had been set up in a most 'Un-English' way, that no one had been deceived, as the two 'witnesses' had known what they were in for, and that they had gone along for their own amusement in a thoroughly underhand business. But the bench were not impressed. Fawcett, they said, had wilfully misled people and the whole thing was 'rather disgusting'. They gave her the option of a £5 fine and costs - about £240 today - or a month in prison.

The court first heard evidence from Clara May Taylor, the wife of a policeman from Earby, who had gone along to see Fawcett with Elizabeth Pye, who was also married to a police constable.

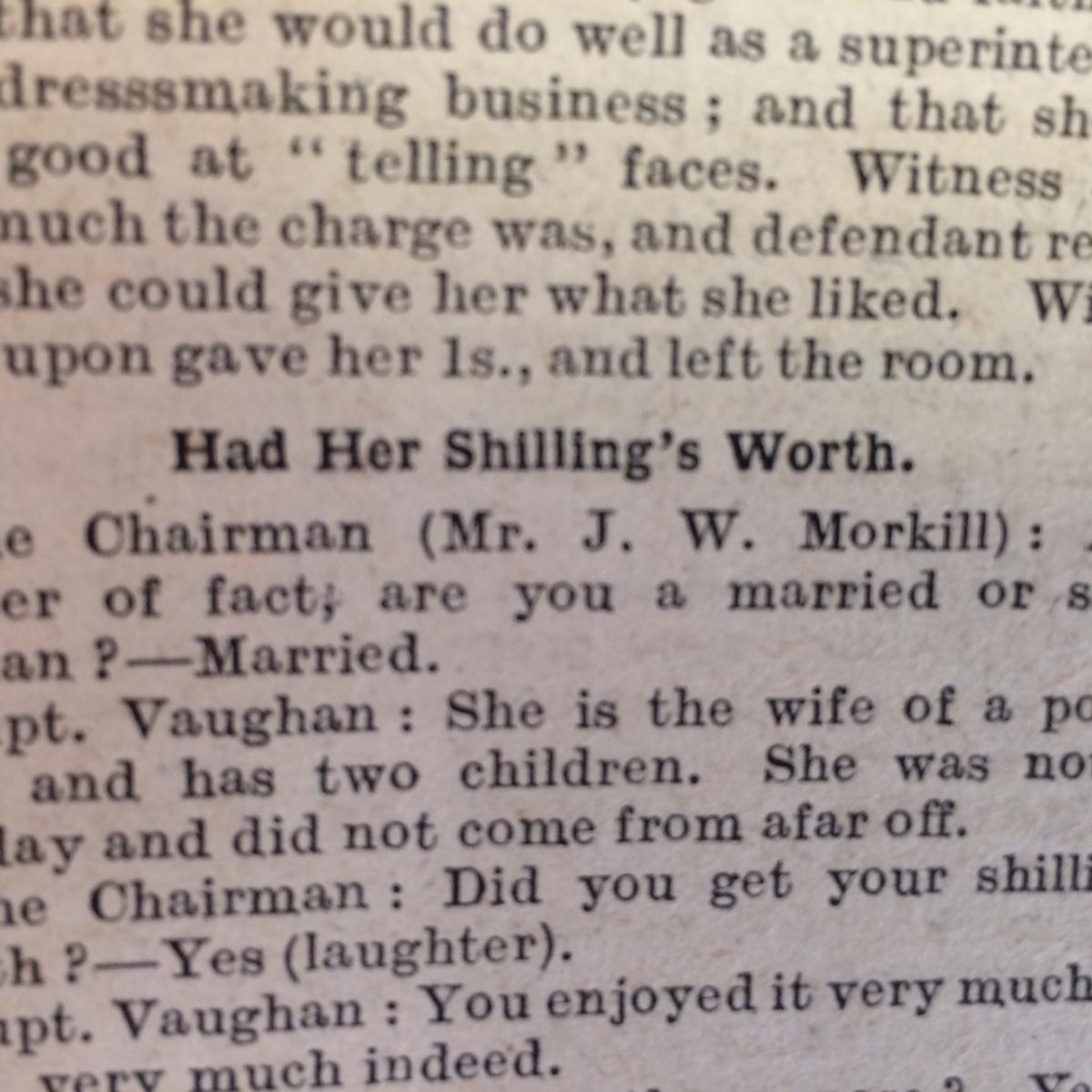

Mrs Taylor described how they had been invited into the drawing room of the house before she had been invited on her own to the upstairs bathroom. Mrs Taylor, who pretended she was single, was asked if she wanted the 'conditions' or the crystal. She chose the 'crystal' and had what she described as a small glass ball - which actually turned out to be a door knob - into one of her hands. After five minutes or so, Fawcett took the ball away and the reading began. There was a man, somewhere between dark and fair, in her thoughts and he would be good and true to her, said Fawcett. They would get married and were assured of happiness. Mrs Taylor was told she would always be successful, as she had a good business head. The man himself was ''well built and broad of shoulder', was sometimes dressed in civilian clothes, and at other times in uniform. Money would come from her sweetheart's family, but only after they were married. There was a woman in her life also who was false to her, and another who was 'sickly' and 'very dizzy'. Switching to reading from her palm, Mrs Taylor was told she was a lady 'from a long way off' who did not like strangers. She would have one or two children, and the man in her thoughts was 'away at present'. Her fortune duly told, Mrs Taylor asked how much, and when told whatever she liked, paid a shilling - about £2.50.

At this point, the chairman of the bench, Mr Morkill, a veteran of many a military tribunal, asked Mrs Taylor if she was a married woman and whether she felt she had got her shilling's worth - to be followed by much laughter from the public benches.

In cross-examination, Mr Robinson asked Mrs Taylor if she had been deceived, and whether she did in fact have a sweetheart, in addition to her husband, to which the answer to both was 'no'.

Mrs Pye described how she had then been invited upstairs to the bathroom and how she had seen two balls on the side of the bath, which she took to be crystals. Fawcett asked if Mrs Pye was married, and when she replied in the affirmative, suggested she ought to have the better crystal - which would cost her two shillings and six pennies, about £5.40 today.

Fawcett placed the 'crystal' in Mrs Pye's left hand, and told her to cover it with her right and left it for a few minutes, after which it appeared to be covered in perspiration. Then, the reading began. Mrs Pye's husband appeared to be very well, but would die before his wife, said Fawcett. He was a 'nattery' man, which Mrs Pye took to mean he was 'cross and tiresome. The fortune teller asked if Mrs Pye's husband was fighting in the war at the time, and when the answer came back 'no' responded he was sometimes in khaki and sometimes in plain clothes. There was also a mysterious 'other man' who was a soldier and very fond of Mrs Pye. He would like to write to her, but was afraid any such letter would 'get into the wrong hands'. Furthermore, he lived close to Mrs Pye, her marriage had been a mistake and she had some money coming to her.

In cross examination, Fawcett's solicitor, Mr Robinson, asked Mrs Pye if she had lied at all during the telling of her fortune, and whether she felt it her duty as the wife of a police constable to go on such missions. The woman responded that she had not lied, and that she did feel it was her duty to help her husband out.

The bench then were told how PC Milburn and Inspector Killeen had later told Fawcett she was to be reported, to which she had replied 'I didn't do much wrong'.

In his conclusions, Mr Robinson told the bench he was not going to dispute the evidence of the two women, but he had plenty to say about how the evidence had been achieved.

He reminded the women they were not acting in the detection of a crime, but had taken part in a crime being committed.

This, he said, was not the 'English' way of doing things and such underhand methods he believed had been condemned by judges in the High Court.

The police and their wives apparently thought they were doing perfectly right and proper in doing all they could in the detection of crime, but they had no right to take part in its manufacture, he went on.

It was un-English, it was not right and they ought not to do it.

Mr Robinson continued Mrs Taylor should not have denied being married, and pointed out such actions could cause misconceptions.

Finally, fortunes had been told, but no one had been deceived, and no charge had been necessary in Mrs Taylor's case, although she had chosen to pay a shilling.

The two women knew perfectly well what was going to happen, and the fortunes told were so absurdly ridiculous and extravagant that they could not possibly deceive anyone.

Mrs Taylor and Mrs Pye had gone for their own amusement in this thoroughly underhand business, he said.

In conclusion, he said the case differed from the London cases everyone had been reading about in the papers, they were of a much more serious nature.

In Fawcett's case, she had carried out her readings in a bathroom, and instead of a crystal, she had in fact used a door knob.

She had been given a home by her brother in law, and unfortunately suffered from a deformity of both hands, caused by rheumatism, was generally weak in health and had no means of existence. She very much regretted what she had done and had learned her lesson. He did not think it deserved a severe penalty.

But, the magistrates were un impressed and called the whole thing 'disgusting'. After imposing a fine of £5 and costs, or a month in prison, they told her she had been guilty of an

impudent imposture - pretending to be someone else in order to deceive others.

She had wilfully misled people to get their money, they said. Fawcett had taken advantage of unfortunate and foolish women who were desperate to seek information about friends or relatives fighting abroad as a way of making money.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here