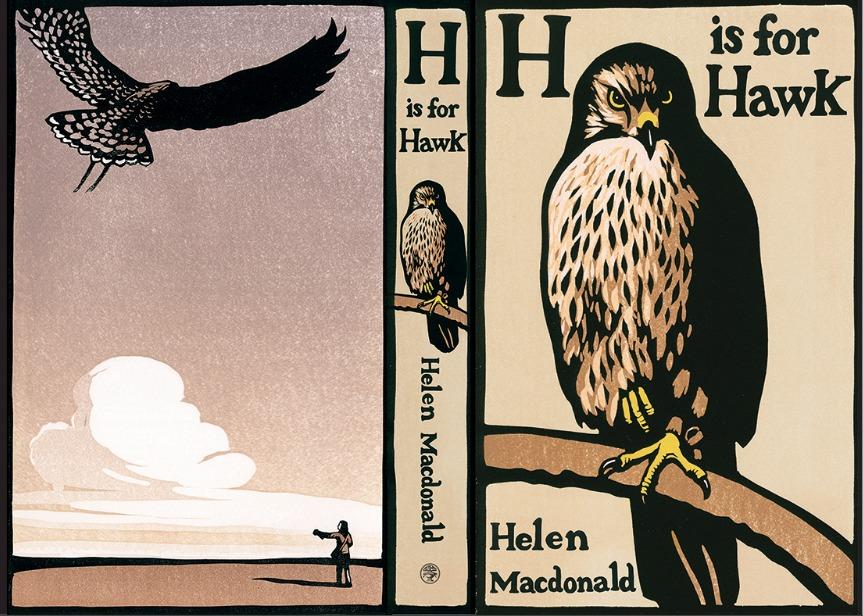

This week Mike Sansbury, of The Grove Bookshop, Ilkley, reviews H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald

Published by Jonathan Cape in hardback at £14.99

BY THE late nineteenth century, goshawks had become extinct in Britain but, thanks to a re-introduction programme in the 1960s, there are now around four hundred and fifty pairs at large in these islands. The writer and academic Helen Macdonald had a keen interest in falconry as a child and, following the unexpected death of her photographer father, found herself drawn to the subject on a more physical level; inspired by reading T.H. White’s autobiographical book The Goshawk, she decided to obtain, train and keep a bird of her own.

This is not a straightforward book, since it follows Macdonald’s shifting mental state as she struggles to cope with her bereavement while learning to come to terms with the needs of a semi-feral bird of prey. Intertwined with her progress on both fronts is a study of White himself, author of The Once and Future King, as he embarks on an attempt to raise his own hawk. The enormity of her decision becomes clear when she finds herself by a deserted Scottish quayside, clutching £800 in cash while a man proffers a cardboard box full of beating, flapping goshawk. The shock she experiences is nothing compared with that of the bird;

“Her world was an aviary no larger than a living room. Then it was a box. But now it is this; and she can see everything: the point-source glitter on the waves, a diving cormorant a hundred yards out; pigment flakes under wax on the lines of parked cars; far hills and the heather on them and miles and miles of sky where the sun spreads on dust and water and illegible things moving in it that are white scraps of gulls. Everything startling and new-stamped on her entirely astonished brain.”

The language she uses to describe the birds is earthy and elemental; slate, flint, pewter and oxblood, while she revisits the childish delight with which she used to relish the arcane terminology of falconry; the jesses, bating,mutes which recall medieval romances in their mystical formation. Like White, who named his bird after Hamlet, Baal, and Tarquin on occasion, Macdonald is drawn to Shakespeare and other poets in her attempts to describe the goshawk’s world. Noting that White sometimes played Gilbert and Sullivan to his hawk, she decides to name her new acquisition Mabel, perhaps only subconsciously aware that it is the name of the heroine of The Pirates of Penzance. This seemingly incongruous choice is merely an adherence to the old falconer’s superstition that, the more harmless the name, the better a killer the bird will be.

Eventually Macdonald reaches the point when her father’s death must be faced, and the cathartic effect of his memorial service is surely facilitated by the relationship which she has developed with Mabel. She makes much of the 1930s cult of the countryside, full of moonlit hikes and train excursions, and she quotes the critic Jed Esty “describing this pastoral craze as one element in a wider movement of national cultural salvage... a response to economic disaster.” We could well be experiencing something similar today, if the plethora of countryside books is anything to go by. Despite this, Macdonald has produced an elegant, disturbing and heart-warming book which never makes the mistake of conferring pet status on what is one of nature’s most lethally efficient killing machines.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here